“Even a fool who keeps silent is considered wise. . .” -Proverbs 17:28

After what happened to Mackie McKennon out at the Natwick dam, everyone stopped speaking to Lester. It was Lester Bracken, his best friend since grade school, who’d been out at the dam with Mackie. It was Lester who reported what happened, and it was Lester everyone agreed deserved the blame.

Sheila Shimroch, who was not yet Mrs. Mackie McKennon number two, and now never would be, went so far as to threaten Lester at gunpoint. Waving a pistol in Lester’s face, Sheila pinned Lester to the hood of the car he’d been gassing up at the Esso station. Sheila kept shouting it would be Lester’s fucking karma if she blew his brains out with Mackie’s very own pistol. The same pistol Mackie gave to Sheila so his soon-to-be ex-wife, Treece, couldn’t find a way to use it on him when she found out about Sheila. Which meant, Lester knew, the gun was unloaded. There was no way Mackie would be fool enough to give any woman he was cheating on—or with—a loaded gun.

But Lester played along, cowering against the car until the checker from the mini-mart took the pistol away from her. The checker didn’t call the cops because she also blamed Lester for what happened to Mackie. Lester didn’t think what happened was his fault, but with so many people being so certain, he was having his doubts.

Lester didn’t force Mackie into the water, or force him over the spillway, or hold him underwater at the bottom of the plunge pool. He’d been the one trying to talk Mackie out of taking a boat onto the river a couple hundred yards up from the dam. How was it people couldn’t understand that?

Mackie was the one true friend of Lester’s childhood, the friend of his school days, the friend through jobs and no jobs, the friend who stood up for Lester at his marriage, drank with him through its failure. Don’t people remember? How is it they could blame Lester for what happened to Mackie out at the Natwick dam?

The Natwick is a low head dam south of the highway. The locals know to avoid it when the water runs high, white, and rowdy, swollen after the warm weather starts melting the winter’s heavy snows. The dam is left over from days when the Natwick mill still stood. The water spills over a drop of eighteen feet into a wide plunge pool filled with old timbers and stonework from the mill when it collapsed. The debris was left there, everyone deciding it was too much work to clear out and cart off. The water back of the ledge is deep and makes for a great place to swim. In the summer the county runs ropes fifty yards back from the ledge to keep swimmers clear of the falls. When the water runs fast, they take in the ropes to keep them from washing away. No need for the ropes. It’s posted no swimming and people know better. Mackie knew better. He’s not an idiot. That’s why he took a boat.

Mackie’s mother, Lester’s second mother through his own mother’s divorce and alcoholic season of rage at men as a species, barred him from Mackie’s funeral.

Lester hung around outside the church, then drove his own car to the cemetery, keeping back from the graveside service. As people were leaving, the Reverend Mobley stopped, gripped Lester’s shoulder, and said, “Every way of a man is right in his own eyes.” He shook his head and gave Lester another quick grip before heading off to find his car.

That killed it for Lester. He chose to spend the rest of the memorial afternoon at the Red Flame, in a back booth with Cliff Hacklett and Ray Wigermeir, who were willing to engage in some recreational grief counseling if Lester was buying. They hadn’t heard the whole story, just the part about Lester being an asshole.

Lester was on his third whiskey, having spent the first two doubles regaling Cliff and Ray with a replay of his and Mackie’s mutually misspent youths.

As if that third whiskey had washed something loose, Lester broke off his meandering down memory lane and got to the main point of his reverie.

“What the fuck’s wrong with people?” Lester asked.

“What did you do out there?” asked Cliff.

“Nothing!”

“Must’ve done something.”

“People’re pretty messed up about it,” said Ray.

So Lester told Cliff and Ray what happened, telling it just like he’d done a dozen times already. When he finished, Cliff and Ray both shook their heads, Ray saying, “Lester, Lester, Lester.” Cliff translated for Ray, saying to Lester, “That’s so like you.”

Then Cliff and Ray said to each other, “Just like the both of them.” They saluted the departed Mackie with their whiskeys.

“What?” asked Lester. “Come on. Like what?”

Lester and Mackie had been drinking and smoking down by the river, which was still running high and fast. Like old times, they were breaking off branches to throw in the river, watching the swift churning current carry their flotsam downstream to the waterfall roaring in the distance.

It had been Mackie’s idea to come down there. For the longest time they didn’t talk of anything much.

Out of nothing in particular, Mackie said, “Talked about getting a motorcycle.”

“What’d Sheila say?” asked Lester, slinging a slice of bark into the water. Mackie had totaled Sheila’s car, and the insurance wasn’t paying for it because Mackie had been driving on a suspended license.

“Same thing Treece used to say. ‘How you plan to pay for it?’”

“Sounds just like Treece.”

“I said I could sell the truck. She says, ‘How’m I supposed to get groceries and run errands?’ Talked about going to Mexico, score some weed to cover it. ‘How long you think you’d last in a Mexican jail? Or even an American jail if you did make it back over the border with it?’” said Mackie, imitating Sheila’s voice. “You believe that?”

Lester didn’t like siding with Mackie’s new girlfriend so soon on anything important to Mackie, so kept his answer to a grunt he hoped sounded like astonishment.

Out of nowhere, Mackie announced that he had never seen the waterfall up close. Lester reminded him that the county had taken down the ropes and Mackie said they only put those up for the pussies.

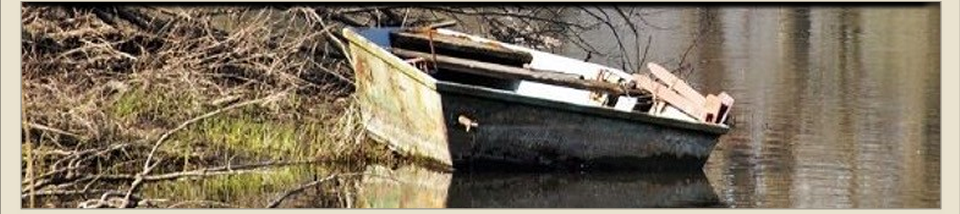

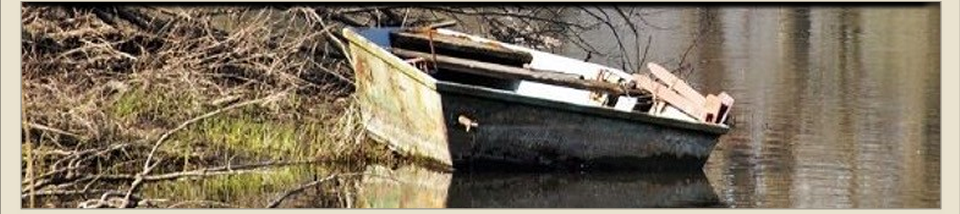

Finding a worn old boat beached from the winter, Mackie said they’d have to hurry before the light failed.

Lester pointed out that neither of them were in any condition to maneuver a boat close in on the crest and avoid the steep drop into the debris-filled plunge pool below. Anyone stupid enough to swim in close usually ended up carried over the edge and broken on the rocks below.

Mackie put his hands on Lester’s shoulders and said, “Wisdom is the pussy, Lester. Ignorance has the balls.”

By the time Lester realized he may have been called a pussy and needed to slug Mackie, the boat had floated free, carrying Mackie downstream. He relaxed in the stern, his feet up on the thwarts, like he hadn’t a care in the world.

Lester stumbled along the overgrown shoreline, running to keep even with Mackie as the boat bobbed and yawed in the unruly current rushing for the falls.

About a hundred or so yards from the falls, Lester shouted to Mackie, telling him to pull in to shore. He was still close enough. Mackie shouted back that he had plenty of time and Lester was a pussy. Lester swore he’d pound his ass, and Mackie invited Lester to come get him.

Lester shouted that he was too close, goddammit, and Mackie mimed paddling the boat like a canoe, his face twisted in the leering grin he had when he was set on some mischief.

Stumbling along, stepping into the slushy pools alongside the river, Lester reached the fallen tree trunk that jutted out from the shore. A great, ancient log, he and Mackie had climbed out to its end hundreds of times. Lester called to Mackie, telling him to get ready and throw the mooring rope. He’d grab it and hold him fast.

Instead, Mackie stood up and danced a sexy cowgirl dance twirling a rope as the boat rocked. Lester started to climb out to intercept Mackie, but the boat was by him and getting closer to the end.

The boat was less than fifty yards from the falls. Lester knew Mackie was strong enough to pull against the current and shouted for Mackie to take up the oars. Mackie mimed deafness, holding a hand to his ear, first one ear then the other ear, then both ears. Lester started swearing, calling him an asshole, and shithead, and moron, furious that Mackie was putting him through this fear that was becoming a terror as the mist of the falls blew toward them, chilling him.

“All right, all right! I’m a pussy! You happy now?” he shouted, hoping Mackie had won from him whatever it was he needed.

Like a man waking from sleep, Mackie took to the oars, and began to row. But it was too late.

Lester thought to swim out to him, and help Mackie row, but worried he couldn’t swim in waterlogged clothes. He tried to run and take off his shoes, struggling with the soaked shoe over the wet sock.

He managed to get one shoe off, then realized Mackie could swim it more easily than he could. Mackie could angle for the shore and let the current carry him in, leaving the boat to go over the falls.

Mackie wasn’t looking at Lester now, so Lester threw his shoe, trying to get Mackie’s attention. But the shoe fell short, its splash lost in the tumult of the water picking up speed as it made for the crest.

The current was too strong, and Mackie was twenty yards from the crest, the relentless momentum carrying him to the falls. Lester could see Mackie realize his danger, rowing for all he was worth.

As if coming to his senses, Mackie stood up to dive into the river and swim for it. At that same moment, Lester cried out to Mackie, “Jump! Jump! Swim for it!” But Mackie sat down and tried to row, failing miserably.

With Lester shouting at Mackie to jump and Mackie rowing like a madman, the boat reached the crest, struck a submerged rock with a chunking thunk that knocked the boat sideways. The bouncing water flipped the boat over and sent Mackie and the boat plunging over the falls.

Lester ran to the point of land overlooking the plunge pool. He saw the boat, bottom up, jammed fast between the rocks, but no sign of Mackie. If he was caught under the boat he’d drown if he hadn’t broken his neck or his back on the shattered masonry or been impaled on an old piling.

He thought to dive in and swim to find Mackie, but the safest water to enter was some thirty yards downstream. Swimming back against that current would be impossible.

It would have been useless, anyway, as it turned out. Mackie had been trapped under the boat and drowned, stuck there until the churning water worked him loose and carried him downstream where campers spotted him and fished him out. He’d been spun out of his shirt and shoes, and his pockets emptied. But the troopers responding to the call put in by the campers recognized Mackie by the tattoos on his neck and arms.

“Why didn’t he jump?” asked Lester, for the hundredth time. “He was ready to.”

“Classic,” Ray said to Cliff.

“Classic. Sometimes, a friend’s so close, he can’t see the biggest thing about a guy.” Cliff said to Ray, both of them nodding to each other.

“What?” asked Lester.

“No wonder they’re blaming him,” Ray said to Cliff.

“Okay, why?”

“Lester—” Cliff started but stopped, his eyes searching overhead. He started again, “Have you ever thrown a touchdown pass in the Super Bowl?”

“No. What’s that got to do with anything? Have you?”

“No. But we all like watching the guy who can. That’s sort of like watching Mackie.”

“He did his own thing,” said Ray, “and looked good doing it.”

“Guy could look good in handcuffs.”

“In handcuffs and naked,” said Ray. “That time, right?” he said to Cliff.

“No one tells Mackie McKennon what to do. People wish they could be like that. Mackie was really good at it,” said Cliff. “Like watching the Super Bowl.”

“You took that away from people.”

“If someone told Mackie to go one way, he’d go the other.”

“Like, you can’t buy beer until you’re twenty-one. Mackie’s right there buying it for you with his id and your cash.”

“Never took more than two for himself.”

“You can’t swim in the city pool naked. Bingo. He’s in there with Rhonna and Clydelia, and Mister Willie dangling in the breeze.”

“You can’t smoke out front of the Piggly Wiggly because that’s where they keep the propane. What’s he do? Lights up and burns the place down.”

“But he wasn’t mean about it.”

“Because it was an accident.”

“Well, they never could prove it wasn’t.”

“And always with a smile.”

“That’s not telling me why he didn’t jump,” said Lester.

“Jeez, Lester, because you told him to,” said Ray.

“I’m his best friend. I’m the one guy he should listen to when he’s being a shithead.”

“You’re missing the point,” said Cliff. “Guy like Mackie? Can’t do what he’s told. By anybody. It’s—biological.”

“You shoulda kept your mouth shut,” said Ray

“And see him go over the falls?”

“At least it would have been his own idea.”

“Hunh.” Lester lit a fresh cigarette, took a long drag and sipped at his whiskey, absorbing this.

“Then don’t take this the wrong way,” said Lester, aiming his finger at Cliff and Ray, the smoke of his cigarette dancing as he waved his finger. “Either one of you ever set yourself on fire, it won’t be me crossing the street to piss on you.”

They bumped fists with Lester and let him buy another round.